Large Banks – A Glass Half Full

In a year with a commodity price crisis led by oil, a surprise vote to exit the European Union by the British and serious China concerns, large bank earnings have actually been reasonably good. Consumer banking in the US is doing well, reflecting a job creating American economy standing alone as the world’s only major market that is balanced and growing. Energy related loan-losses are minor and not the dire results contemplated in January. All of the large banks bought back large blocks of their shares. Bank of America bought $1.4 billion of its stock last quarter and given its depressed price, it represented 1% of shares outstanding. When it comes to bank cash flows to investors, what actually is happening differs from headline angst about American banking.

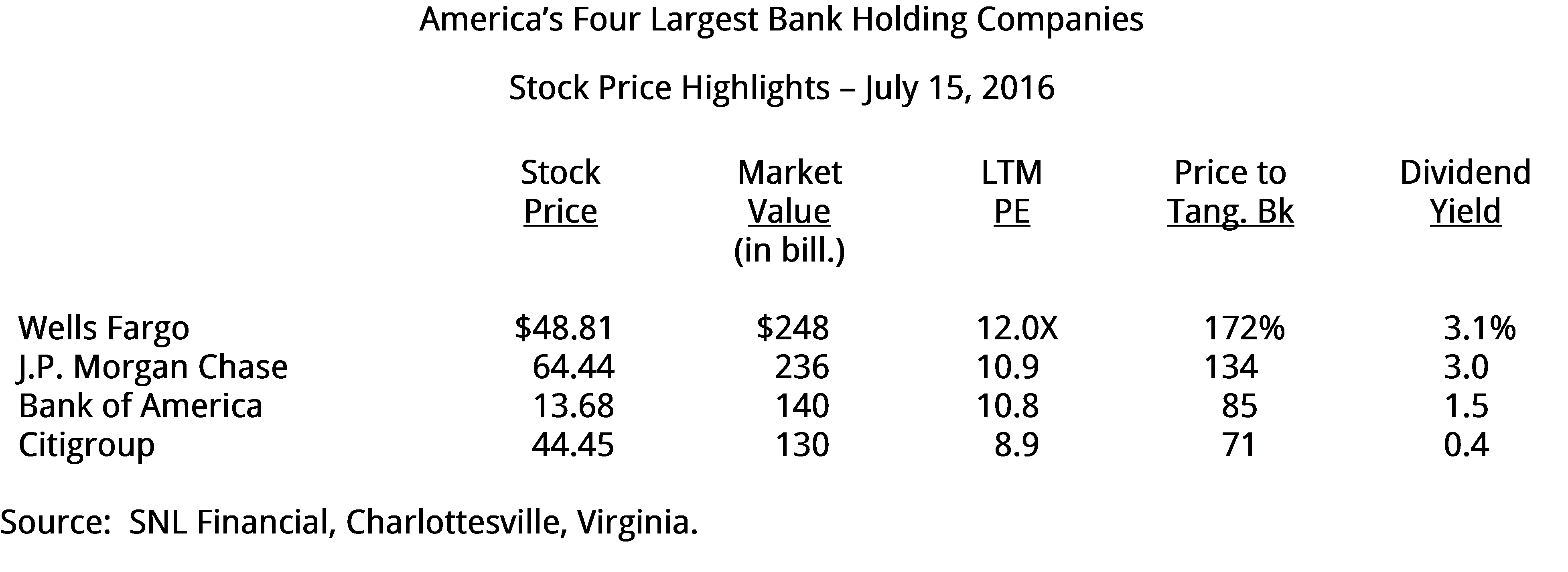

A snapshot of large bank valuations as they were reporting second quarter earnings shows a bifurcated market. Wells Fargo and J.P. Morgan Chase traded at 11 to 12 times earnings, 3% dividend yields and at premiums to tangible book per share. Bank of America and Citigroup had much lower dividend yields and traded at discounts to tangible book. In market value Wells Fargo was worth almost as much as Bank of America and Citigroup combined!

A snapshot tells only so much. In 2016, Bank of America traded as high as $16.45 and as low as $10.99. The high price, recorded in the first days of January, suggested a company on the mend trending toward its more valuable peers. The low price, recorded in February, suggested a company at significant financial risk. Do the shifting perceptions of the macro economy justify such stock movements?

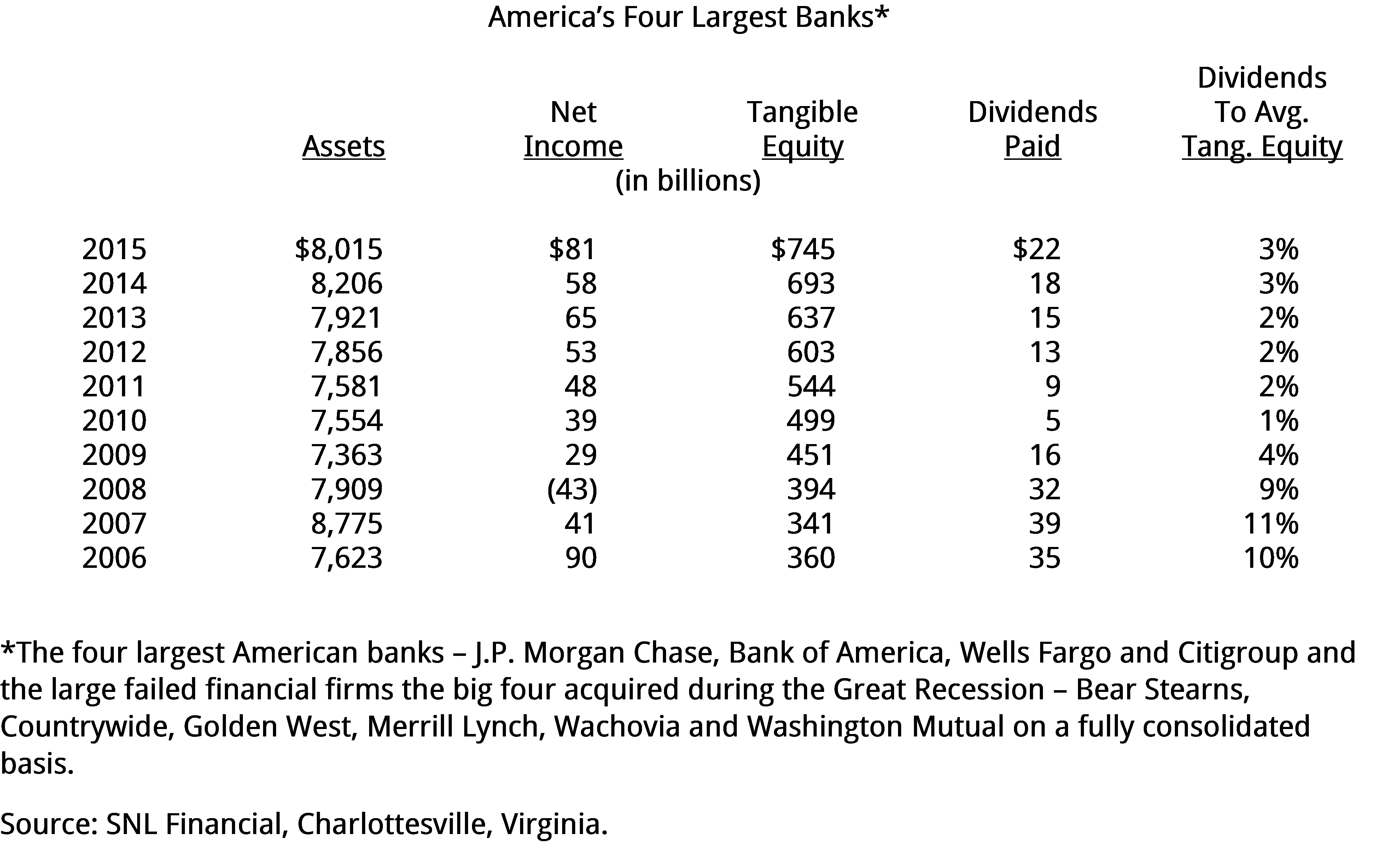

A little historical perspective helps. The business model of the large banks changed in the wake of the Great Recession. In 2006, the four largest banks, plus all of the large companies they would acquire during the crisis, earned $90 billion on a capital base of $360 billion. This was roughly a 1.2% return on assets and 25% return on capital and by any measure very high financial returns. Fast forward to 2015, the large banks earned $81 billion on capital of $745 billion. This is roughly 1% on assets and a hair above 10% return on equity. Not a terrible return, but 2015 was the best the large banks posted by a wide mark since the Great Recession.

The change in relationship between dividends and capital is a stunner. In 2006 dividends to capital for the large banks was 10% and in 2015, it is 3%. The reason is simple math. Capital has doubled and dividends are down by almost half. The ten year table also reveals the large banks made their own bed. In 2008 and 2009, the large banks paid out $48 billion in dividends even as the nation’s financial bedrock shook. In the bizarre world of banking, the perception of strength (we are paying dividends) was deemed more important than actual strength (we have more capital).

The Federal Reserve seized upon this industry failure and uses it to justify absolute control over cash flow utilization by the large banks. Since 2009, the Federal Reserve’s Stress Tests have for the most part declared the industry sound and reasonably capitalized. Yet since 2009 capital for the large banks has been driven up from $450 billion to $750 billion, or roughly 67%. Almost all of this has been accomplished through retained earnings. There has never been as much capital in the banking system as there is now.

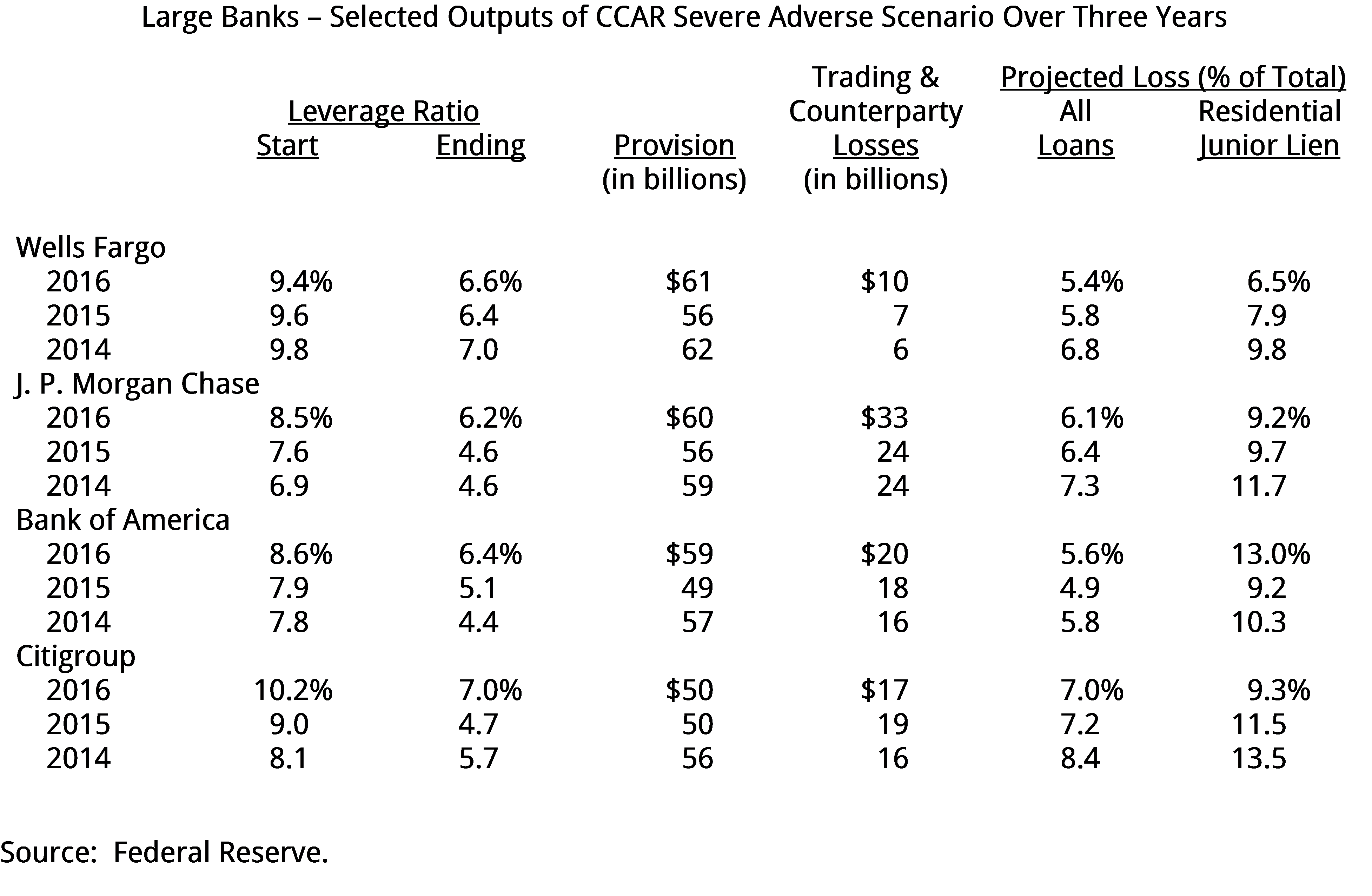

The Federal Reserve and the large banks expend a tremendous amount of effort annually to generate the granular data that purports to model the impact on the large banks of an economy going through a fictitious egregious recession. It is all very complex and sophisticated, but look at the output over a three year period.

The forecasted loan losses for Wells Fargo, J.P. Morgan Chase and Bank of America is basically $60 billion in all years. Citigroup is a little lower at $50 billion. In 2015, Bank of America’s estimated provision fell out of range, their capital plan was not approved and bang, the next year the provision jumped right back up. Some of the loss rates don’t make sense on a standalone basis. In 2016, Bank of America’s projected loss rate in the severely adverse scenario on junior lien residential housing is 13%, up from 9% in the previous year, and double the rate of Wells Fargo’s 6.5%. Apply Wells Fargo’s rate to Bank of America and the projected provision falls $5 billion, which aftertax is more money than Bank of America’s annual dividend.

Defending or attacking the individual pieces of the Stress Test isn’t the point. The Stress Tests are not about getting it “right.” They are geared to substantiate a proximate amount of loss to justify building capital in the system. The overall trend is obvious. All of the large banks are headed to a 9-10% leverage ratio, and Federal Reserve officials have intimated as much in their speechmaking.

The idea that more capital is always better is powerfully simple and politically appealing. However, it’s causing two severe problems for the long term. The first is it shifts focus away from the real problem, which is risk management. Wells Fargo and Citigroup both conducted hundreds of billions of residential loan transactions in the years leading up to the Great Recession. The former came through the ensuing recession with some scratches and dents and $57 billion in provision expense, while the latter drove the bus off the road, hit a tree and had $97 billion of provision expense. Although 10 times leverage is less risky than 15 times leverage, capital is false comfort when levered companies fail in risk management. The $40 billion of additional provision at Citigroup was due to shoddy risk management, no matter the amount of capital.

The other problem is if banks don’t make much money in relation to their capital, then investors don’t provide new capital when it is needed. This is currently happening in Europe. Not only are Greek and Italian banks starved for capital, but so is Germany’s Deutsche Bank. Stock prices are so miserably low that even when recapitalized, it’s difficult for many European banks to show a reasonable return, particularly in the prevailing extremely low interest rate environment.

The investment logic of a low earning bank in the current regulatory regime is a spiral down. In the event of losses, low earning banks have trouble covering the losses with earnings. When losses are made good, building capital to higher standards is difficult, time consuming and leads to miserable IRR calculations.

This logic explains what is going on with our largest banks. Wells Fargo and J.P. Morgan Chase have been able to demonstrate a decent profit for the risk they are taking. If the economy turns a little sour, investors can see a path for them to earn their way through it. Dividend payments at 3% are attractive in the low rate environment and reasonably safe given dividend payouts are only about 1/3 of earnings per share.

Bank of America careens between stock highs and lows because it hasn’t demonstrated a consistent profit commensurate to the risk taken and capital required. When the economy suddenly looks riskier, like in January when high energy credit losses were deemed likely, Bank of America’s weaker earnings make it seem more vulnerable. Wells Fargo, which actually has higher energy exposure, seems more likely to investors to power through problems. Second quarter earnings for Bank of America were pretty good, pointing to a stabilization of its earning potential at about $1.60 per share annually. The stock has dutifully responded pushing back to $15.

The primary path to higher returns on 9% to 10% leverage ratios for large banks is severe cuts in services and expenses, substantial branch closings and higher fees. The new found profitability of the airlines built on incessant fees and bare bones service is a good analogy for what the large banks will serve up in coming years to consumers. When it comes to large bank stocks, the new normal is investors being constantly afraid of their own shadows, but the most likely result is an acceptable parade of mediocre earnings, dividends and share buybacks that is actually pretty good when compared to all the other lousy returns the market currently has on offer.

Logically, you can turn a lot of the headwind arguments against the large banks into tailwinds for community banks. Smaller banks have always carried more capital than their larger brethren, so the 9% to 10% leverage standard isn’t a new challenge to the business model. Small banks don’t have the same liquidity constraints as large banks allowing them to use higher loan to asset ratios to stave off margin compression. Community banks are not being artificially growth constrained, so in dynamic urban markets we are seeing impressive amounts of profitable growth. Large banks have little more to gain from scale efficiencies, while smaller banks can grow and merge to rapidly increase efficiency and profitability. Community banks are prime beneficiaries of the cheap money and cheap energy, which are having such a positive impact on US employment and US residential markets. This is a different and local story that isn’t in the headlines much compared to the far more common stories of banking angst.