Long in Tooth

Nine years of economic expansion makes investors anxious. Expansions generally don’t last this long without a setback. Some market analysts are forecasting a “likely” recession in 2020. Given the poor record of economists in forecasting recessions, is this purely speculative? Does the length of an expansion give insight into what comes next or is it like flipping a coin and getting nine straight heads, a happenstance which would induce many people to bet, incorrectly, the next result must be tails (the odds are still 50)?

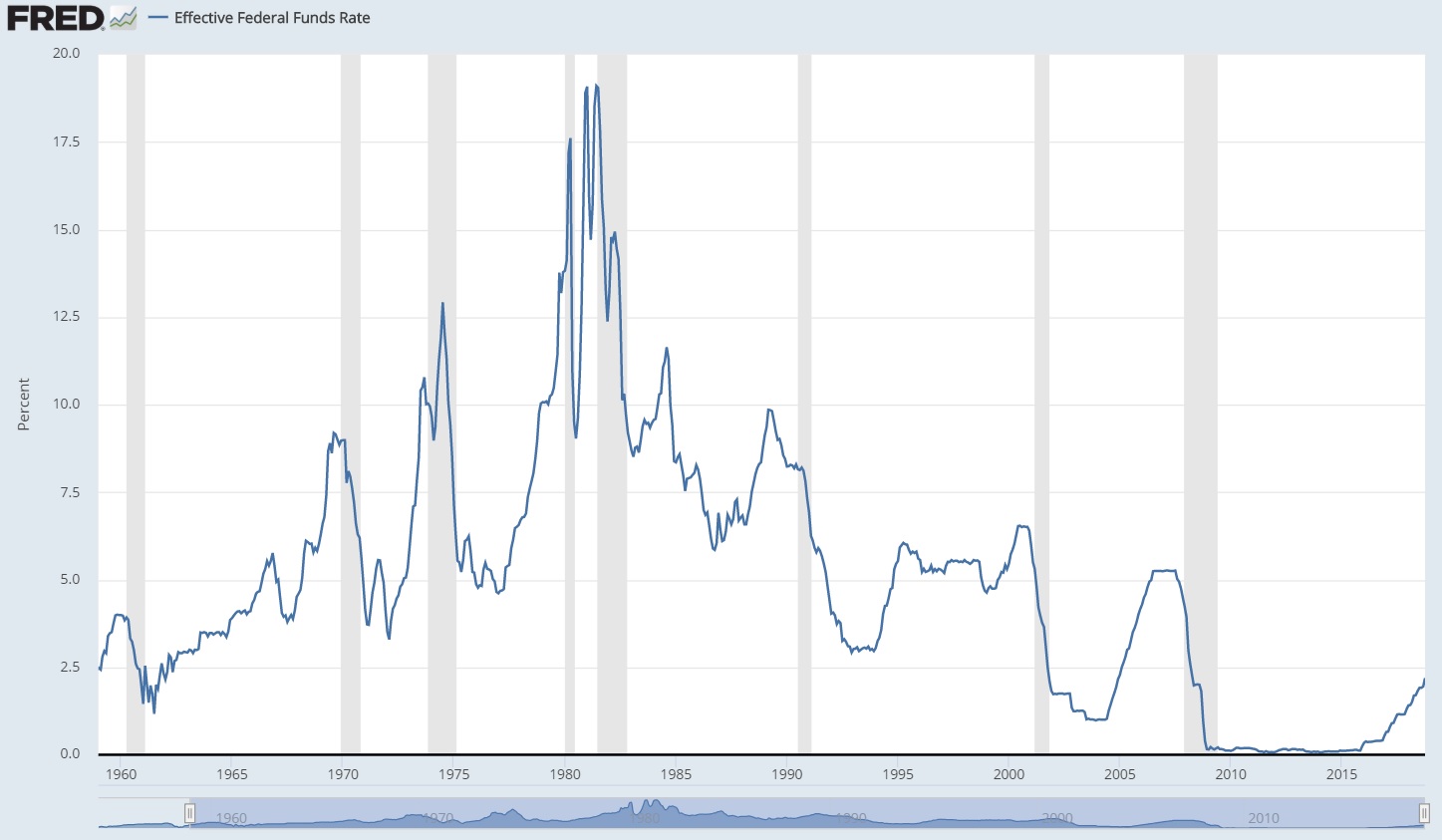

Although economists have a poor record of forecasting recessions, even the deepest ones, economic history does offer a guide as to what to look for if a recession is around the corner. Since 1960 there have been seven periods of recession, which makes the average expansion about eight years. In the year before a recession, interest rates were rising in every case. We currently meet both of those tests. Four other times, though, rates were rising and subsequently fell again without recession, which is a high error rate if rising rates is your only predictor. The entire 1960s expansion, almost ten years, occurred with rising rates year after year.

Fed Funds Rate 1960 to Present

Recession Periods Shaded

When the Federal Reserve raises interest rates, it is trying to restrain inflation. In the best case the Fed can accomplish its inflation goals without causing recession, something it did in 1995, but not infrequently the Fed induces a recession instead of a soft landing. The recent stock market pullback began when Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell answered a reporter’s question by stating that interest rates were “a long way from neutral.” This suggested many more rate increases were ahead even as market observers have begun to note areas of economic weakness caused by how far interest rates have already risen.

When the Federal Reserve raises interest rates, it is trying to restrain inflation. In the best case the Fed can accomplish its inflation goals without causing recession, something it did in 1995, but not infrequently the Fed induces a recession instead of a soft landing. The recent stock market pullback began when Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell answered a reporter’s question by stating that interest rates were “a long way from neutral.” This suggested many more rate increases were ahead even as market observers have begun to note areas of economic weakness caused by how far interest rates have already risen.

Rate trends and expansion length isn’t a lot to dig into, though, so let’s put faces on the seven modern recessions. The 1970 recession was primarily a response to the controlling of budget deficits stemming from the Vietnam War. The 1974-5 and 1979 recessions were led by Arab Oil Embargos and the skyrocketing cost of oil. The 1981-2 recession was engineered by the Fed to end a period of very high inflation, sort of like taking one’s medicine. The 1990 recession was a real estate bust coinciding with post-Cold War fiscal reductions. The 2001 recession followed the Nasdaq Tech bubble and the 2008-9 recession followed a residential housing bubble.

The three most current recessions involved bubble prices in a major asset class, with housing being the most devastating, while the four recessions between 1970 and 1984 stemmed from inadequacy on the supply side of the economy. The underlying cause of a recession is critical in how it plays out and how damaging it is. Not all recessions are created equal. If you ranked the six recessions relative to their overall negative impact, the 2008 recession stands above all and the second worse was the inflation shock in the early eighties. It may not be coincidental that the two “major recessions” coincided with a generational shift in the direction of interest rates and inflation.

Equally instructive from past recessions is that in most cases the cause for the recession was visible beforehand, even if people did not act on it, or perhaps failed to act. In 2006, it was common knowledge houses were trading at prices well above any period in history. The same was true of the inflation crisis in the early eighties and the budget imbalances of the Vietnam War.

This suggests the imbalances which could play a role in a near future recession should be observable right now. Based on what is visible today, there seems to be two paths that may take the economy toward recession. The first is certainly no surprise, which is the federal budget deficit. The recent tax cut reduced federal revenues by $100-$150 billion annually, widening an already significant deficit. The tax cut makes the budget math more difficult, but it’s not the heart of the problem. The corporate tax cut is a Hail Mary at generating rapid economic growth to overcome the real problem, which is entitlements.

The pay-go system whereby today’s taxpayers pay for today’s pensioners has reached its endgame. Medicare and social security taxes were in surplus the last two decades as the very large baby boomer generation hit peak earning years, subsidizing the general budget. This has now reversed, with the baby boomers retiring and a much smaller generation X following it. A smaller generation simply can’t pay for a larger generation without large deficits. It is a fixable problem, but party politics make a near term solution unlikely.

The logic of an entitlement/deficit driven recession, though, does not imply anything in the near future, which is why even pessimistic pundits target 2020 as the earliest year for recession. The $18 trillion US economy growing at 3% can carry this year’s $800 billion deficit, so pessimism is built on the trends, not where the US stands today.

Even as the deficit promotes pessimism, it is possible to be optimistic about the lack of a visible price bubble in a major asset class. Tech stocks are deflating, but tech stocks are still in positive territory for 2018, so much higher declines would be necessary before their decline becomes more than a marginal economic driver. There is a bubble deflating in bitcoin, but it’s not big enough to tip the economy.

If not the stock market, then perhaps the other major issue in the news could be a recession driver, which is trade. It is hard to get fact-based observations about trade given the lack of any modern history of tariffs rising between major economies. It was more distressing when Mexico, Canada, Europe and China were simultaneously in trade disputes with the US. With NAFTA resolved and Europe in abeyance, the confrontation with China seems less dangerous. It’s a difficult situation to predict because the trade dispute is politics more than economics.

Our feeling is that trade uncertainty isn’t the biggest worry of investors relative to China. It’s generally recognized that the trade flows being affected aren’t big enough to drive the US economy down except on the margin – maybe 1% GDP annually on the high side.

There is a big and highly visible worry, though, and it is frequently reported in the American press. The Chinese economy carries a great deal of debt and their financial and real estate markets are opaque. It’s cliché for Wall Street Journal reporters to refer to Chinese state-owned companies as propped up. There are many reports of “shadow-banking” trusts raising money to invest in high risk real estate projects. Even Sixty Minutes has covered the “ghost cities” of China, built but unoccupied. Recently the Chinese authorities have placed heavy restrictions on the Fintech sector after the discovery of an $8 billion Ponzi scheme in peer-to-peer lending. All of this raises the specter of a real estate crash crushing the Chinese bank sector, and the economy in general. China’s economy is more than twice the size it was just ten years ago, and that kind of rapid growth can cause misallocation of resources.

If the one, two punching team of Trump and Pence succeed in kicking in China’s teeth and get a “good deal,” the result might not be what is expected. The Chinese economy may convulse into a debt crisis dragging others with it. History is full of examples of questionable policy aggravating serious problems before they are recognized as such.

The interesting thing about this discussion around the length of the economic expansion is how quickly one abandons the premise once you consider the details. Based on past evidence that imbalances which drive recessions are visible, a nine year expansion is not correlated to the ability of the US political system to balance entitlement revenues and expense. The nine year expansion didn’t start the trade war with China, nor did it cause the debt imbalances in the Chinese economy, which have been built up over a multi-decade expansion.

Policy will likely determine the probability, duration and depth of any recessionary period and this is comforting. The Federal Reserve can moderate the pressure of interest rates by slowing or eliminating rate increases, something alluded to by Chairman Powell last week, and the US can tackle entitlement reform as it did in the 1980s. Trade policy can be settled with China, as it has with Canada and Mexico or it can become more thoughtful as in the case of Europe.

Investors in our opinion should take a measured approach when evaluating their positions. Some amount of rising rates is still the most likely path for the next year, so the durability and price of an investment needs to be measured against that reality. Our feeling is that rates have already risen to a point where it’s impacting the economy, particularly real estate. The real estate market has had ten years with rates between 3% and 4%, and it will struggle to adjust to a higher 5% to 6% range. It also means we may be closer to the end of the tightening cycle than most people thought even a few weeks ago.

Higher interest rates and a slow growth economy favor companies with strong core earnings and limited need for financing. In the bank sector, financials with core deposits will benefit from stable or wider margins, while banks dependent on wholesale funding will tend to suffer as rates rise. As mentioned previously, rising rates pressure sectors that require leverage to make sales, such as housing and auto, and the industries that rely on housing and auto. General Motors’ announcement of a major restructuring is evidence of this pressure.

Given the poor record of economists in forecasting recessions, we feel investors are better off analyzing their portfolio for strengths and weaknesses relative to rising rates and making adjustments rather than sweeping changes, particularly fear-based selling, which triggers taxes and uncertainty around reinvestment. The recent market adjustment is healthy, and it is revealing good values. Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway invested billions into the American banking sector in the third quarter and this is a good example of putting aside fear in the search for quality, long term investments.