Reversion to the Mean

Last August we described large banks as a glass half full. At the time Wells Fargo and J.P. Morgan Chase were the premium franchises in investors’ eyes, so much so that Wells Fargo’s value was almost equal to Bank of America and Citigroup combined, a stunning statistic. In the last several months, the financial sector has had a great run. The catalyst for the move was the election of Trump and a Republican Congress opening the door to regulatory relief, tax cuts and reflationary government spending pushing up interest rates.

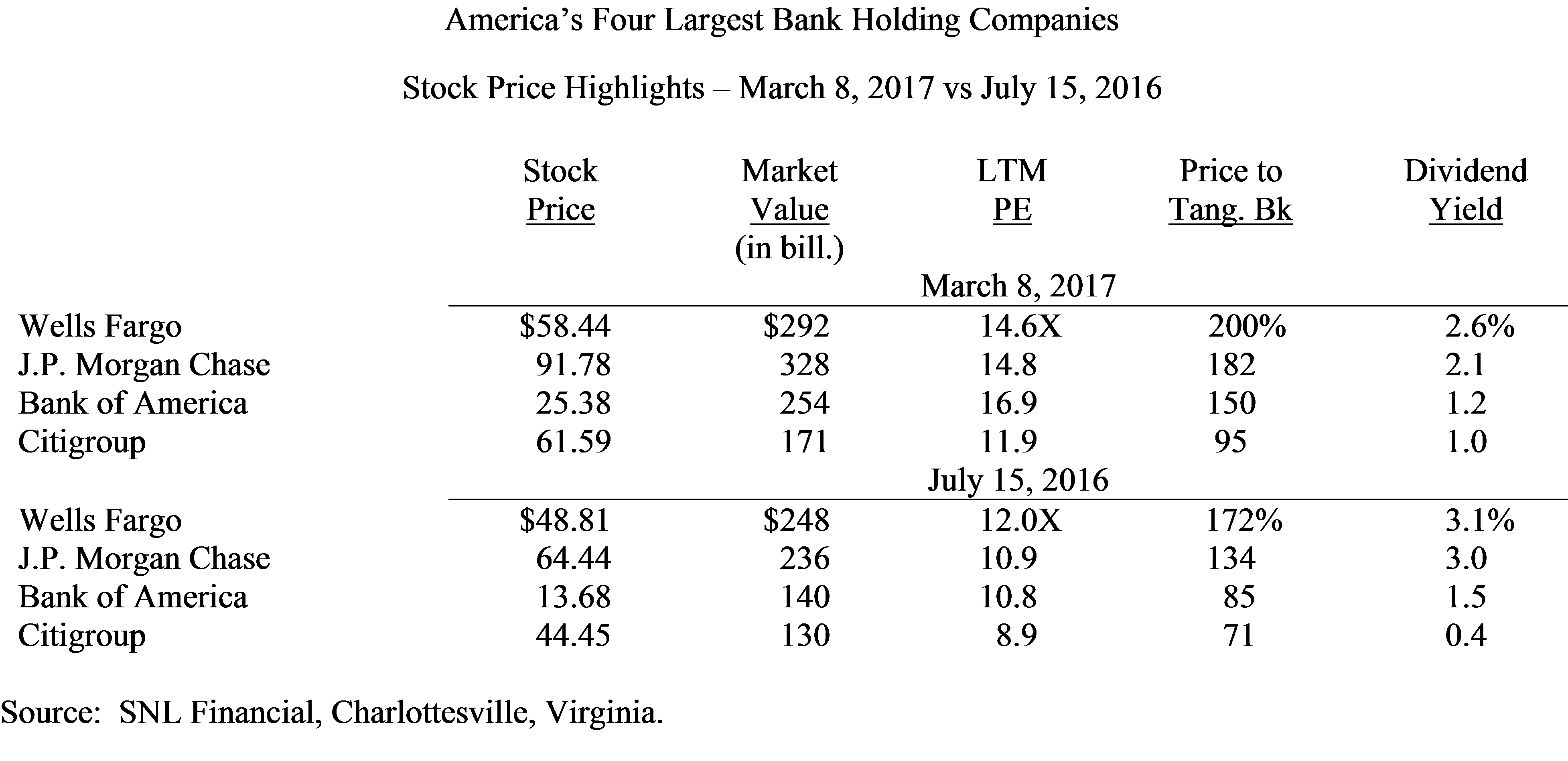

Within the fundamental financial sector move, though, a common investment principle is at work – reversion to mean. While Wells Fargo remains the most valuable franchise measured by price to tangible book, its recent stock value rise of 20% pales in comparison to that of Bank of America, up almost 100% and less than half of J.P. Morgan Chase’s move of 50%. These changes have made Bank of America and Wells Fargo much closer in market value and moved J.P. Morgan Chase to the top of the heap in terms of overall valuation.

After the financial crisis in 2008-09, Wells Fargo and J.P. Morgan Chase were elevated in the minds of analysts and investors for their savviness in avoiding the worst of the downturn. Jamie Dimon proclaimed his “fortress” balance sheet and John Stumpf bristled at Wells Fargo being forced to take TARP capital. J.P. Morgan Chase completed two government assisted deals – Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual – at little cost. Wells Fargo swiped the floundering lemon, Wachovia, from a government-assisted Citigroup deal, and made lemonade. Investors were pleased when both companies rapidly reintroduced a significant dividend. Their stock prices recovered much of the ground lost in the recession by 2011, and both trade much higher than their former peak values in 2007.

This relative outperformance of J.P. Morgan Chase and Wells Fargo led analysts and reporters to construct causal stories for the success. Risk management was better. Culture was stronger. Management was superior. The truth was simpler. J.P. Morgan Chase and Wells Fargo did have risk management, culture and management. They did lever these strengths during the financial crisis into making value creating acquisitions. With little dilution to their stocks during the crisis, it was only a matter of time before the value of these acquisitions showed in performance and stock value.

Before the financial crisis, Bank of America was reasonably equal in culture and risk management to these other two franchises. If Bank of America had minded its knitting while the financial world teetered on destruction, it probably would have come out equally well, but it didn’t. The company made two disastrous acquisitions – Countrywide and Merrill Lynch – without government assistance. The losses generated by these deals put Bank of America in the dog house for seven years.

Whatever the causal stories generated by analysts and reporters for the greatness of J.P. Morgan Chase and Wells Fargo vs the ineptness of Bank of America, it was a matter of time before the pig moved through the snake and the value of Bank of America showed itself. After all, it’s not like J.P. Morgan Chase employs 200,000 stars and Bank of America employs 200,000 dopes. The three franchises have particular strengths and weaknesses, but overall they are in the same business, have about the same scale and similar earning potential. Bank of America is reverting to mean by rising.

Wells Fargo is showing us the same principle, but in the other direction. The “fake accounts” scandal tarnished their reputation and halted their growth. Although still the highest valued franchise measured by price to tangible book, Wells Fargo has relinquished its lead in total market value to J.P. Morgan Chase and is a scant $50 billion ahead of Bank of America. This is a far cry from where they stood last year on a relative basis.

In the last five years, the highest large bank stock price increases are Bank of America at 210%, SunTrust at 161% and Regions at 157%. All three franchises were damaged during the financial crisis and traded at low prices to tangible book for several years thereafter. The fact that all three have now risen to the top as the best place to invest for the highest gain (risk and volatility be damned) is not surprising. Reversion to mean has turned out to be a more important principle than the pervasive pessimism that reigned for years over these three franchises based on supposedly causal qualitative differences.

Understanding the process under way in the financials is also the best prism for understanding the overall stock market. The stock market as measured by the S&P 500 and Dow Jones Industrial average has been setting new highs of late. Both indices are up close to 10% since Trump’s election. It is fashionable for business reporters to talk about the irrational exuberance and likelihood of a near term decline. However, instead of focusing on the overall market, consider the different sectors.

As we have already discussed in isolation, financials are up big. The sector has moved 25%. Half the move in the S&P 500 is the financials. Just the large banks discussed above are up more than $300 billion in market value. Throw in the large regional banks and insurers, and the gain goes above half a trillion. These companies are not suddenly trading at unheard premiums to earnings or book, but they are reflecting the strong potential for rising interest rates improving the operating earnings and lower corporate taxes improving the dividend payout and stock buyback programs.

It is hard to overstate how difficult the last several years have been for the banks given extremely low interest rates. Initially in 2009-10, lower rates expanded margins, but this boost expired relatively quickly and five years of near-zero interest rates has challenged the fundamental banking model. It extended the amount of time necessary for the large banks like Bank of America to earn their way through their problems. It is more difficult to make money when it costs 100 to 200 basis points to provide deposit services to clients, yet wholesale money costs less than 50 basis points. It’s a little bit like the business of gold mining. If the price of gold falls below the cost of mining it, gold producers can’t make money. The mines stay open only because of sunk costs and the hope that supply and demand will eventually balance causing prices to rise. This is the moment that has arrived for banking.

Community banks, in particular, have been hard pressed for several years. Community banks are high cost providers of deposit services because they are less scaled, and tend to be more branch centric. Most community banks get more than 80% of revenue from spread income. When the Federal Reserve chose to keep interest rates so low for so long, community banks and savers, were among those “thrown under the bus”. Second guessing the Federal Reserve’s policy really isn’t the point. It is simply to note that rising rates is as significant to community banks as $50 oil is to the health of the oil industry. Community banks as a group have been a weak segment since the financial crisis because low interest rates harm the business model. The group is now reverting to mean.